New research may pave way for octopus aquaculture

October 16, 2019

By

Liza Mayer

The chances of an octopus surviving beyond early paralarva stage are very slim, making the Spanish achievement a major breakthrough

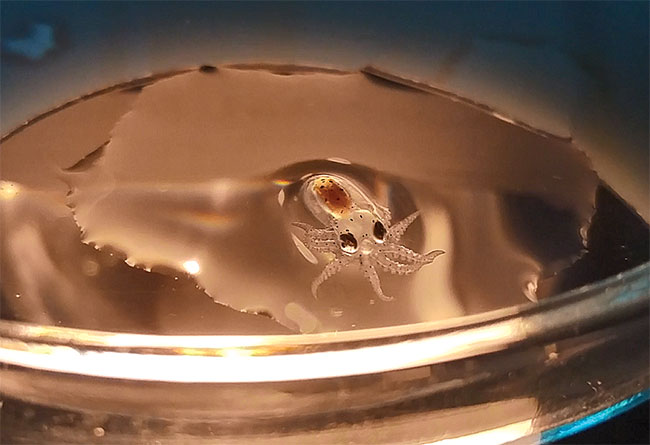

Credit: Nueva Pescanova Group

The chances of an octopus surviving beyond early paralarva stage are very slim, making the Spanish achievement a major breakthrough

Credit: Nueva Pescanova Group Efforts to farm octopus have reached a major breakthrough with the spawning of octopuses in captivity.

Researchers at Nueva Pescanova Group in Spain announced in July that 50 octopuses of the common variety (Octopus vulgaris) that were born in captivity in 2018 have matured. One of them has even laid some eggs.

The achievement is noteworthy because the chances of an octopus surviving beyond early paralarva stage are very slim. “The octopus requires very specific marine conditions for development, such as the availability of food and optimal oceanographic factor connected to temperature, salinity, ocean currents, and the animal’s wellbeing,” said Ricardo Tur, principal investigator on cephalopods at Pescanova.

This challenge has hindered the development of fully closed lifecycle octopus hatchery systems. In fact, according to the researchers, the survival rate of a wild octopus is 0.0001 percent. With the results that Pescanova is obtaining until now, the survival rate of farmed octopus could go up to 50 percent, the researchers said.

They acknowledge more R & D needs to be done, including improving the octopuses’ wellbeing and replicating their natural habitat. They expect, however, to start selling farmed octopus starting in 2023.

Currently, commercial aquaculture of octopus relies on juveniles caught in the wild, but the practice is unsustainable and costly to farmers. This, as well as growing demand from consumer markets—Spain, Japan, South Korea, Greece—is prompting R&D in octopus aquaculture.

The milestone comes after decades of research at different centers and companies around the world. The Spanish Oceanographic Institute initiated the research and saw the survival of juvenile specimens born in captivity. Pescanova took over the research from the institute and advanced it at its own facilities. The company will open the Pescanova Biomarine Center next year, which will have the cultivation of octopuses as one of the main lines of study.