Larger trout bring more money

January 17, 2017

By Ruby Gonzalez

Study’s findings will benefit producers who need a set timeframe to achieve a specific fish size

Study’s findings will benefit producers who need a set timeframe to achieve a specific fish sizeUnderstanding trout’s economic and performance traits throughout the production cycle and its impact on product efficiency is vital to a profitable operation, according to Beth Cleveland, a growth physiologist with the USDA National Center for Cool and Cold Water Aquaculture.

Cleveland presented her study, “What Size to Harvest Rainbow Trout/Steelhead in RAS? Consider Growth Rate, Feed Conversion, Fillet Yield, Fatty Acid Deposition, and Production Efficiency,” at the 2016 Aquaculture Innovation Workshop held in August in Virginia.

She cited an interesting point about the relationship between fish growth and feed conversion throughout the grow-out process.

“We see elevation rates in the food conversion ratio (FCR), which is not desirable, as the fish gets larger,” she said. It must be noted that the higher FCR, the lower the weight gain obtained from the feed. “But these increases are offset by increased product yield. And that offsets the increase in cost.”

To illustrate this, she showed a “highly simplified economic model” that factors in the different market rates for rainbow trout and steelhead, differences in the types and yield of the products. Rainbow trout had a harvest size of 500 g, and steelhead, 1 kg and 3 kg. The three each had a 1,000-ton volume harvest.

Bigger is better?

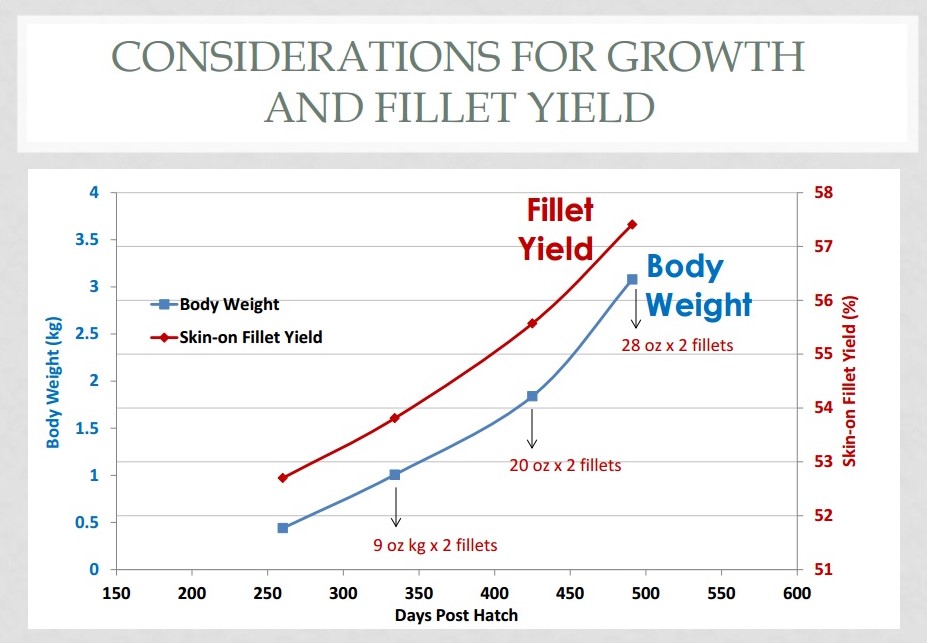

The 1-kg steelhead had a fillet yield of 53.8 percent and the 3 kg, 57.4 percent. Not surprisingly, the revenue from the latter turned out higher. Another advantage it had was that because it was larger, it commanded a better price.

Despite having the largest volume of product, because of its 58 to 68 percent butterfly fillet yield, the 500-g rainbow trout posted the lowest revenue because its price per pound was much lower.

Propping revenues, however, is “not as simple as scaling up production.”

The critical factors to consider are changes in growth rate, reductions in FCR with age, changes in product yield and product quality.

Rainbow trout is usually sold as a butterfly, skin-on fillet. Cleveland said 50 percent of the output is grown by Clear Springs, which supplies national restaurant chains like Cracker Barrel and Red Lobster. “This leaves smaller producers and new producers to find different markets, mostly local supermarkets or the local white-tablecloth restaurants.”

Per anecdotal report, she said steelheads are sold as part of the commodity market, thus enjoying a higher demand. The downside is that the price fluctuates; it follows the price of the Atlantic salmon.

“Steelhead is often produced with a large, skin-on beautiful fillet. It is a lot like salmon. That’s probably why it follows the trend of the salmon market,” she said.

Food conversion ratio

While steelhead is priced about 10-percent lower than salmon, when raised in RAS, it posts a rapid growth trajectory. It could be harvested at 3 kg after 17 months. It takes salmon about 21.5 months to reach that weight. “There is much earlier increase in growth performance in the steelhead and get them to the market faster,” she said.

The rainbow trout and steelhead were studied in the Freshwater Institute’s RAS tanks. Throughout the study, the selected harvest weights were 500 grams, and 1, 2 and 3 kg.

Growth and feed conversion are directly proportional throughout the production cycle.

Compared to the period between 500-g to 1-kg body weight, FCR posted a “dramatic increase” between the 1- and 2-kg. “This will certainly affect the amount of feed purchase.”

The basis for increased FCR are feed intake, digestible energy, metabolizable energy and net energy.

FCR is all about how energy is transferred and how it adds to growth formation. “Sometimes, it doesn’t even have the chance to get into the fish. This passes out as fecal matter,” she said, referring for food intake. “The difference between energy consumed and energy that’s available for use is the digestible energy. Energy is also lost through excretion whether in the form of urine or through the gills. Energy is also heat. Heat is given off. Heat is energy. So, energy is lost,” she summed up.

“Most of the energy is lost through maintenance. This is the amount of energy required just to maintain biomass of the fish. A larger fish requires more energy. This also includes voluntary activities like swimming, and thermal regulation. Whatever is left over after energy is allocated to all these essential processes, is what’s left over for growth,” she said.

Optimum feeding satiation

Cleveland explained that maximizing the amount of energy the fish consumes can improve FCR. This includes increase in nutrient and energy density of the pellet.

“Fish are slightly different from mammals in that if the mammals consume a very energy–dense diet, they correct that by reducing food consumption,” she said. Thus, pellet size must be optimized to fish size.

Feed must be formulated according to palatability and ingredients that increase amount of digestible energy. Cleveland said ingredients that are not very digestible contribute to diarrhea and, eventually, loss of nutrients through fecal matter.

Understanding nutrients demand is also important. Citing protein-to–fat-to-carbo ratio, she said, “Too much fat will contribute to visceral fats and reduction in fillet yield. Too many carbo can lead to fatty liver syndrome.”

When it comes to feeding regime, there are two options: the low-dose, high-frequency approach and high-dose, low-frequency approach.

The study revealed a new way at looking at fish feeding satiation.

While most of the previous studies were completed by feeding fish to satiation, Cleveland and her team had observed that optimum feeding satiation doesn’t occur at 100 percent of satiation but at 75 percent. Specific growth rate, however, is achieved at 100 percent of satiation.

Feed cost reduction

She said these facts will be help producers who need a set timeframe to achieve a specific fish size.

“For example, if a fish needs to get at 3 kg at a specific time, it is more beneficial to feed a fish to a small level of moderate feed restriction during this time because this will result in improved feeding procedure,” she said. This is a better approach compared to feeding the fish through satiation, reaching market weight too early and then feeding maintenance ration through the remainder of the period.

Four percent less feed was consumed in this method, saving the producer $50,000 in feed cost.

Ultimately, the harvest size depends on what the consumers want.

The small rainbow trout butterfly fillet is usually served pan-friend and enjoyed for its light, delicate texture. The larger steelhead has firm meat and resembles salmon.

For increased appreciation of the different sizes that the fish can offer, she suggested that producers could provide recipe cards or other educational materials to make sure the consumers understand what they are getting.

— Ruby Gonzalez

This article was based on the video and PDF presentation uploaded by the Conservation Fund’s Freshwater Institute in its website.