Deepwater oceansphere one step closer to reality

September 2, 2014

By Erich Luening

Hawaiian company will start construction next year of prototype offshore yellowfin and big eye tuna farm.

Hawaiian company will start construction next year of prototype offshore yellowfin and big eye tuna farm.With an eye towards the infrastructure necessary to grow tuna offshore, the aquaculture technology firm Hawaii Oceanic Technology, Inc. plans to build and operate a yellowfin and big eye farm in deep water off the island of Hawaii.

The company says that it plans to start construction next year, with fish going into a prototype Oceansphere after a six month trial period.

“Our permit allows for 12 [spheres], but we’re just going to build one sphere to test and prove the concept,” Hawaii Oceanic Technology (HOTI) founder Bill Spencer told Aquaculture North America. “Cash flow from initial sales will contribute to build-out. The opportunity to do it in the open ocean is our focus.”

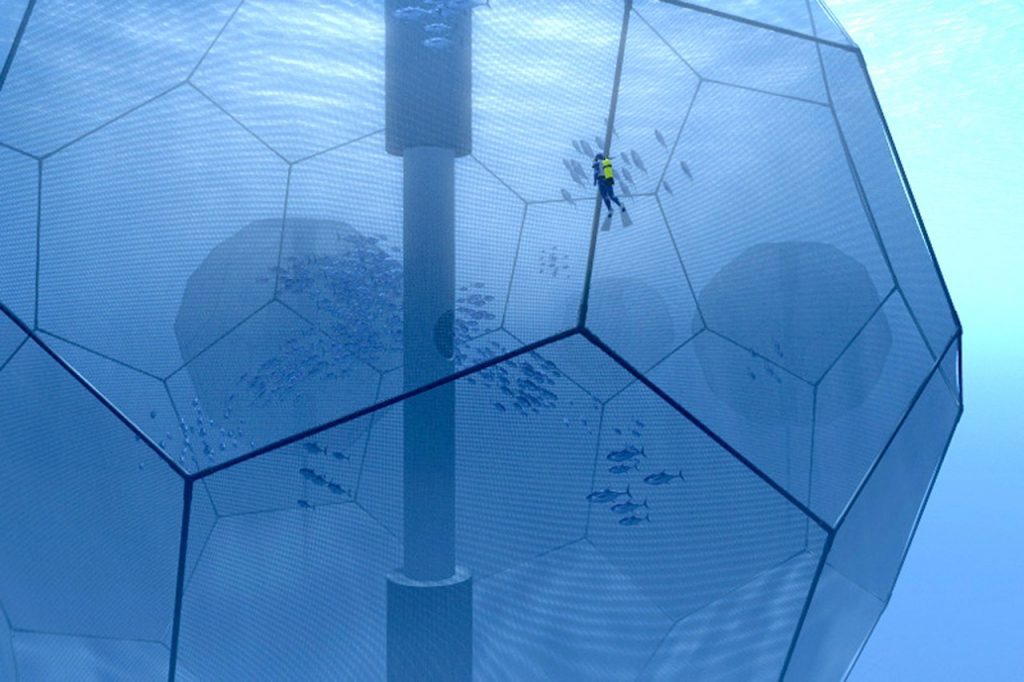

HOTI contractors are working to finalize the design for the skeleton of the 180-foot wide geodesic sphere which will contain yellowfin and big eye tuna, also called ahi, Spencer said. The company is betting on the earlier spawning age of yellowfin and big eye to find better success than the mixed-results of bluefin farms in Asia.

The deepwater pen will be capable of holding 1,000 tons of ahi at a submerged depth of 60- feet. Fish grow faster in deep ocean settings, have fewer parasites and better food conversion ratios, according to the company.

The company, the first sanctioned offshore tuna farm in U.S. waters, received its final permit from the Army Corps of Engineers last year in a plan to build up to 12 of the spheres in a 247-acre area about three miles off of Malae Point near Kawaihae.

Broodstock and eggs

There are also plans to build a HOTI hatchery in the future to supply juveniles to the farm, but for the first phase over the next couple years HOTI is working with Syd Kraul at Pacific Planktonics, which has over 30 tanks on a half-acre of land leased at the National Laboratory of Hawaii in Kona. He has been working with yellowfin eggs and larvae since 2012.

“Rearing the larvae is still a challenge for all the tuna hatchery efforts worldwide,” Kraul explained in an email. “Nobody is doing much better than Kinki University in Japan, at about 0.5% survival of eggs to weaned juveniles. The exception is (was) Bent Urup’s 2011 work with Futuna Blue in Spain, where one batch of 15,000 eggs yielded 2,000 (13%) small juveniles that would have been big enough to wean if they had feed on hand.”

Kraul’s method uses the same key ingredient as Bent’s, i.e. copepods, which have proven superior for larval rearing in many species, but are more difficult to culture than standard hatchery feeds.

He said he believes Spencer’s wish to have ahi in the first Oceansphere by 2018 is very possible as long as funding remains consistent.

“If Bill needs 18 months for growout, then I have a year to prove the method, following which Bill would build a larger hatchery of his own and work out any startup kinks.” Kraul said. “I think that is entirely possible if we can get some tuna eggs for testing. Unfortunately, it has been hard to get tuna eggs on a low budget, hard to get money without showing first that hatchery methods work.”

Kraul is in the process of getting more tuna broodstock to test a less costly way to produce eggs.

“I am fairly certain (thanks to Bent’s tests) that my method will yield about 10% larval survival, possibly more. I am not as certain that we will have a steady supply of eggs,” he said.

Regulatory hurdles

The multi-million dollar project will employ an automated feeding system and a series of thrusters to keep the sphere stationary. A network of sensors will provide constant data on water quality, as requested by the Environmental Protection Agency, Spencer said.

“We expect to include a whole package to transmit data to a centralized monitoring system,” Spencer explained. “This allows operators to provide data to regulators and also reduce infrastructure costs.”

Some residents still remain hostile to the project, according to local reports. About 1,700 people signed a petition opposing the farm, and in 2012, 400 people wrote letters to the state Board of Land and Natural Resources opposing extensions of construction deadlines that the board granted while the company waited for clearance from the Corps of Engineers.

That said, Spencer had good things to say about the state and its support for aquaculture all around.

“Hawaii has a mature regulatory infrastructure,” he said. “I would say, number one, we have been held to the highest standard and have been able to meet expectations. The state understands the economic advantages of offshore aquaculture for the island. Second, it is one of the largest EEZs (Economic Exclusion Zone) around Hawaii. We could be exporting product from here.”

The feds on the other hand weren’t as easy to work with,” Spencer lamented. “There’s no rush there. If it takes four years, it takes four years, and it’s very frustrating. Overall we are very excited we met the requirements and are excited to get moving.”

— Erich Luening