Research project showing potential for farming Blue crab

June 25, 2019

By Bonnie Waycott

Blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) have played an important part in Mississippi's history and economy for years. Consumers enjoy the species as appetizers and seafood products, but blue crab populations in the wild are declining, putting a strain on local fishermen.

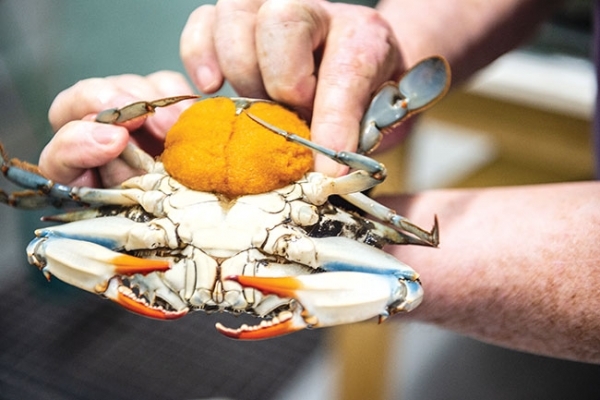

Female crabs carry their eggs externally

Female crabs carry their eggs externally Established in the early 2000s, the University of Southern Mississippi’s Blue Crab Hatchery is working to make farmed blue crabs a reality. It’s hoped that these efforts will allow fishermen to supplement their income by developing fisheries based on cultured blue crabs.

“The idea took off when wild crab harvests in Chesapeake Bay were really low,” said Dr. Kelly Lucas, aquaculture director at the Thad Cochran Marine Aquaculture Center in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. “The University of Maryland worked out techniques to mass-produce blue crab larvae to experiment with supplanting the wild harvest in the Bay. Our hatchery was established using protocols developed by the Maryland facility with modifications to those protocols, based on data gained from years of experimentation.”

Hatchery

The current research program is based on a three-phased approach: hatchery production, intermediate raceway grow-out and a final grow-out in quarter-acre ponds to a soft crab or a live bait crab for recreational fishing.

“We have six independent larval rearing systems, seawater preparation and storage, rotifer (Branchionus rotundiformis s-type) and Artemia production, and wet and dry laboratories,” said Harriet Perry, senior research scientist and professor emerita at the University of Southern Mississippi’s Gulf Coast Research Laboratory. “Each culture system consists of a 1,400-liter fiberglass larval rearing tank with 1,000 liters of water and a round 400-liter filter reservoir tank. The reservoir tank has a trickling biofilter, protein skimmer and activated carbon/crushed coral up-flow filter.”

Seawater (28‰) is prepared with filtered, dechlorinated city water. There are also semi-continuous, high-density rotifer culture systems in place with a 200-liter cone-shaped culture tank, oxygen concentrator, feeding pump, air supply and heater. The heaters maintain water temperature at 25°C and the Artemia culture system includes a water table with five 20-liter cone-shaped hatchers.

Spawning

Females with recently laid egg masses are obtained from commercial fishermen, disinfected, held in individual quarantine tanks and examined for parasites and disease. Crabs free of disease are transferred to 100-liter hatching tanks for spawning. The spawn of a single female is used to stock tanks. Female crabs are then returned to the wild. Newly hatched zoeae are fed rotifers.

Larvae

Zoeae are harvested with netting, counted and placed in culture systems at 100,000/system (total culture capacity is 600,000 individuals). The systems are pre-stocked with feed – 50 million enriched rotifers and algae.

“During the later stages, zoeae are also fed adult copepods and newly hatched and enriched Artemia once a day,” said Perry. “Daily plunge samples are taken from the tanks to determine the zoeae’s stage of development and number, and the number of rotifers and Artemia. Temperature, salinity, pH, ammonia, nitrite and nitrate are monitored over the culture period. Tanks are harvested following the appearance of the final larval stage, called a megalopa, usually within 24-30 days of stocking.”

Megalopae

Harvested megalopae are placed in 6’x 22′ raceways with ~8,000 liters of seawater. Structure (pom-poms) is added to the tanks to provide refuge and reduce cannibalism. Temperature, salinity, pH, ammonia, nitrite and nitrate levels are monitored regularly. Juveniles are fed pelleted food, frozen Artemia and copepods, with feeding regimes adjusted to coincide with predicted growth.

After the first week of grow-out, freshwater is added to the systems to gradually lower salinities and allow juveniles to acclimate from 25‰ to 3‰. They are then transferred to low salinity ponds (average depth is three feet) at the Mississippi Department of Marine Resource’s Aquaculture Facility near Gulfport. Artificial sea salts are added to bring the salinity to 1‰. A diet of pelleted finfish is given during the first week at 15 percent of body weight, followed by small, aquacultured koi from week two until harvest. The crabs are stocked at 2,500 to 3,000 crabs per quarter-acre pond.

The ponds that produce bait crabs contain submerged aquatic vegetation. Smaller crabs are fished out with minnow traps, the larger ones with crawfish traps and sub-adult and adult crabs with standard crab traps. The ponds that produce soft crabs have no vegetation and crabs are harvested using bushlines that are run twice a day to check for crabs that are molting. Those showing signs of shedding are removed and the days until molting estimated. They’re then transferred to closed recirculating seawater systems. The length of stay in the ponds varies and depends on temperature and size requirements for production.

A sustainable alternative

The Blue Crab Hatchery’s main goal is to support the livelihoods of blue crab fishermen in Mississippi.

“We’re working to offer another economic opportunity for fishermen or farmers,” said Lucas. “Farming can supply bait crab production for anglers, and cocktail or smaller soft shell crabs for the restaurant market. Some fishermen may decide to farm crabs and some farmers may diversify their ponds by adding crab production. Therefore, it could be another income string for fishermen at a time when it’s not conducive to be on the water, while people who farm can add a new product. Our technology is very much in the developmental stage but there have been a lot of people who are willing to try it and want to diversify.”

The road ahead

Lucas says there are two challenges to overcome: cannibalism and maintaining broodstock.

“First, we need to develop a captive broodstock program to control production year round,” she said. “We are looking to start such a program. We have a geneticist at the Aquaculture Center and the reproductive physiology of blue crabs is known. We’re working to find funding for this aspect of the research.”

“Megalopae, juvenile and adult crabs are highly cannibalistic, and this greatly increases mortality,” she continued. “But there are ways to reduce cannibalism, like decreasing stocking density or providing shelter in tanks.”

It may be some time before the researchers have the answers they need, but Lucas has high hopes for their work. Following the recent funding of a joint National Sea Grant proposal with North Carolina, Perry, along with the crab team, will work with the NC researchers and private industry to transfer their hatchery and production technology to the Atlantic Coast.

If their research pans out, more blue crabs in the U.S. could be the result of a new, thriving industry.