Offshore aquaculture plan for Gulf of Mexico

November 25, 2014

By Erich Luening

In view of the benefits of employment and secondary spin-off industries created by offshore aquaculture

In view of the benefits of employment and secondary spin-off industries created by offshore aquacultureAs the Gulf of Mexico offshore aquaculture plan moves through the necessary federal approval process, a look at the economic impacts to the region finds negative and positive outcomes, based on the most recent research by government and academic bodies.

The National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) public comment period on the latest version of the Fishery Management Plan for Regulating Offshore Marine Aquaculture in the Gulf of Mexico ended October 27th, but conclusions on what the economic impacts of a new Gulf offshore fish farming industry are few as researchers find limited offshore aquaculture in other parts of the U.S. to use for baseline economic numbers.

In 2008, NOAA highlighted the challenges in analyzing the potential economic impacts of offshore aquaculture in the U.S.

There are “three major challenges in assessing the economic potential for U.S. offshore aquaculture,” agency researchers wrote in the report ‘Offshore Aquaculture in the United States: Economic Considerations, Implications & Opportunities.’ “These are: 1) the limited experience to date with offshore aquaculture and the likelihood of continued change in key factors affecting economic potential, including technology, feed costs, and markets; 2) the diversity of potential types of offshore aquaculture; and, 3) the importance of the regulatory regime in affecting economic potential.”

That said, because of the global demand for more and more seafood and the growing U.S. multi-billion dollar seafood trade deficit, the economic potential is there for a vibrant offshore aquaculture industry in the country.

But let’s start with the limits to adequate research in this area.

In the most recent economic impacts analysis conducted by the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, researchers were straight forward in the inability to come to any conclusions.

“There is presently no finfish aquaculture in the Gulf EEZ,” council researchers stated in the report, ‘Economic Effects of Gulf Aquaculture Amendment.’ “Consequently, the portion of the economic baseline attributable to existing finfish aquaculture in federal waters of the Gulf of Mexico is zero: zero landings, revenues, profits, employment, and other economic benefits, and zero economic costs. However, there are commercial finfish aquaculture operations in state waters.”

The federal government and the University of Mississippi SeaGrant office have provided a little more substance than the Gulf council report.

Impact potential

The 2008 NOAA report, looked at three fish species—Cod, winter flounder, and atlantic salmon—to estimate and assess the potential economic contributions of finfish aquaculture. They used the Beverton-Holt model, a “classic” discrete-time population model, first used in wild fishery population estimates, which gives the expected number of individuals in a generation as a function of the number of individuals in the previous generation. They also used various feed conversion ratios to help with the cost of feed. All the species looked at as part of this model were based on a 15-year period as a baseline assessment period at a proposed farm.

Revenues were estimated using price times quantity on a monthly and then annual basis.

The Atlantic cod model farm produced 177 metric tons, or 390 thousand pounds per month for a total of 4.7 million pounds a year. Revenues for the model cod farm was $13 million. That’s just based on one generic sized offshore farm.

The Atlantic salmon model farm was assumed to produce salmon on a year-round basis. The expected harvest of salmon was 4.5 million pounds. The salmon farm was expected to generate revenues of $8.1 million per year.

For the winter flounder farm, which stocking and harvesting is restricted to two two-month periods per year, was projected to produce 3.3 million pounds of flounder per year with sales of $15.2 million.

Looking at those 2008 figures for just three model farms, producing three different species, none of which will likely be farmed in the Gulf of Mexico, it shows that any regional offshore aquaculture market will see hundreds of millions of dollars of potential impacts for the regional economy. And that’s just in actual sales of product.

In a 2005 report, ‘Potential Economic Impact of Commercial Offshore Aquaculture in the Gulf of Mexico,’ by Mississippi State University’s Coastal Research & Extension Center and the state’s Sea Grant Extension Program, an attempt to give a more regional perspective was tried, using industry multipliers tied to the well established commercial fishing industry in the Gulf as well as agriculture data under the “miscellaneous livestock” sector.

“What [offshore aquaculture] does is revitalizes coastal economies and fishing communities by providing employment and secondary spin off industries,” said Neil Simms, Hawaii-based Kampachi Farms owner. “Fishing industries and their support multipliers have been reduced because of the current status of wild fisheries. Offshore aquaculture here in Hawaii has helped stimulate employment in both the actual fish farming and in the secondary industries as well.”

The Mississippi State University study, conducted by Benedict Posadas at the coastal research center, also used pilot mariculture projects done over the years in the region as data sets for potential economic factors. The “spin-off” sectors potentially impacted by offshore aquaculture include, but aren’t limited to, farmed fish product transportation from the farms, to processors, to wholesalers, and to restaurants.

“Economic benefits from aquaculture production accrue not only to those directly involved in the industry but contribute to increased employment and revenue of the entire region through multiplier effects,” wrote Posadas in the intro to his study. “Aquaculture can also supplement domestic fisheries, increase seafood production and provide stability for the seafood industry.”

In fact, recreational and some commercial fishermen could find an increase in their wild fish production.

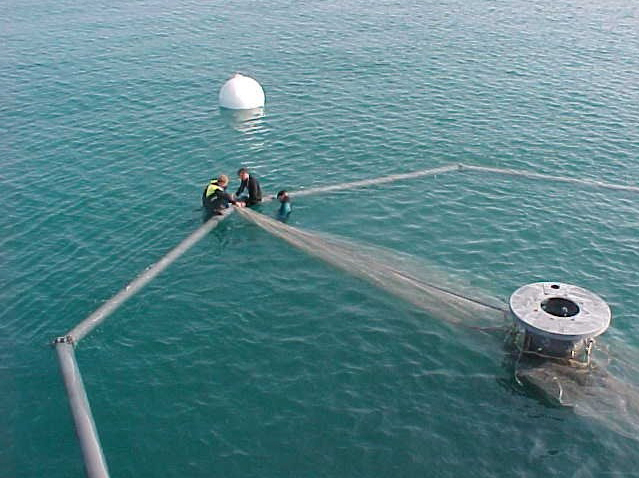

“Here in Hawaii what we have seen in recent projects is that the experimental metal cages have become fish oasis and aggregators,” Sims said. “Commercial fishermen and small scale charters as well. That’s important to help them understand that aquaculture can be a benefit for them as well.”

Posadas looked at cobia, red snapper, and red drum as candidate species for offshore aquaculture in the Gulf as part of his study. The hypothetical fish farms consisted of 12 cages which would require an initial fixed investment of $3.8 million each.

“The annual economic impact to the Gulf of Mexico region of single 12 cage offshore aquaculture production system would range from $9.1 million to $10.2 million,” Posadas concluded.

In comparison, the 2005 study showed the commercial fishing industry for the three candidate species in the Gulf of Mexico at that time, which were, and continue to be limited by state and federal fisheries regulations, which created an economic impact in the region amounting to $20 million.

The subsequent primary processing and wholesaling of all food fish species, from both the cultured and caught enterprises, in the Gulf of Mexico created a total impact reaching $80 million in 2005 dollars, according to the University of Mississippi Sea Grant analysis.

— Erich Luening

AUTHOR’S ADDENDUM

Gulf Offshore Aquaculture Plan critiqued by Hawaiian expert

Offshore aquaculture advocates have issue with a handful of rules in the latest version of the Gulf of Mexico Aquaculture Fisheries Management Plan.

The director of the Ocean Stewards Institute (OSI), an advocacy group for offshore aquaculture and Kampachi Farms in Hawaii, Neil Sims told Aquaculture North America the group has some pointed concerns with the plan, like permit tenures, production capacity limits, the ability for the NOAA regional administrator to cancel permits, and limits on recreational fishing in aquaculture areas, among others.

OSI shared its concerns to NOAA before the deadline of the public comment period on October 27th.

The issue Sims finds with the current version of the plan is in the rules as presently drafted.

First, the offshore aquaculture permit tenure as laid out is to short. The current restrictions on the duration of the permits—an initial period of 10 years followed by a renewal every 5 years—is seen as a disincentive to any long-term investment capital.

“They risk confounding the ultimate goal of building an industry by stifling the opportunity for attracting investment capital,” said Simms. “If investment capital is the air that an industry needs to be able to grow and thrive, then the insistence on a short permit duration could well strangle this industry at birth.”

Second, Sims found fault with limits on the volume of fish any offshore farm can produce under the plan.

“That seems silly, given a U.S. seafood deficit of over $11 billion, and growing,” he said. “It’s also a disincentive for investors.”

Third, Sims has a problem with a regional administrator who, under the plan, may deny a permit if issuing the permit would result in conflicts with established or potential oil and gas infrastructure.

“Grounds for denial include if the permit might prevent an expansion of future oil and gas activities or any conflict with recreational and commercial fisheries,” Sims said. “This is overly broad. No one industry should have prior claim to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) waters of this nation and the permit applications should therefore be equally considered for all EEZ user groups, unless there are operational or safety conflicts.”

And finally, the plan requires that there be no fishing allowed inside the permitted area of an aquaculture site. Sims thinks that shouldn’t be a universal mandate.

“By denying permit applicants any ability to reach a compromise for negotiated access with recreational fishermen and women, this rule will create division and animosity in the coastal community, where there is no need.”