Skill, not tech, strongest success factor for RAS, finance expert says

June 24, 2020

By

Liza Mayer

Not overnight but overtime, operators will get it right, says global investment firm

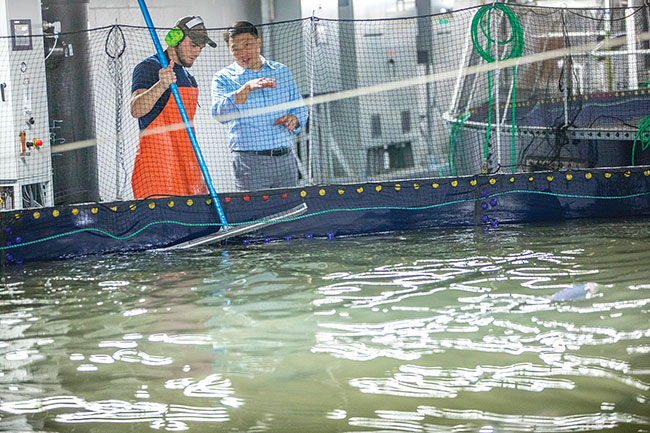

Hudson Valley Fisheries CEO John Ng, seen here with staff at the family-owned farm in Upstate New York, wants to help build a RAS-savvy industry workforce Photo: Hudson Valley Fisheries

Hudson Valley Fisheries CEO John Ng, seen here with staff at the family-owned farm in Upstate New York, wants to help build a RAS-savvy industry workforce Photo: Hudson Valley Fisheries It’s easy to think that it’s technology that will make or break land-based fish farms but it isn’t the best gauge of whether a project will succeed — it is people, according to Roy Høiås, founder and CEO of global investment firm Lighthouse Finance.

Høiås cut his teeth in the RAS space when he tailored financing solutions for some of the early land-based RAS (recirculating aquaculture systems) facilities built in Scandinavia more than 10 years ago. His firm is currently involved with roughly 10 technology providers and seafood producers that are creating land-based growout solutions in various parts of the world.

In his backyard in Norway, he says the question in most people’s minds is not “if” RAS will work in growing Atlantic salmon to market size, but “when.” And having the right people to run these operations plays a critical role.

“That’s where we see the biggest challenge in the market today. We are quite confident that grow-out farming is not a technology issue, it is a knowledge issue,” Høiås tells Aquaculture North America (ANA).

“You need knowledgeable, experienced people that not only understand biomass, but also understand how to utilize RAS technology to maximize the environment for the fish. That (talent pool) is still a young part of the industry that needs to develop and will develop in the next two to three years.”

Høiås and Lighthouse’s Managing Partner of Global Capital Markets, Howard Tang, shared their insights on RAS after Atlantic Sapphire announced in March the loss of 227,000 fish in its land-based facility in Denmark. The salmon farmer attributed the mortalities to high nitrogen levels.

Høiås says such incidents underscore there’s still plenty of work to do. “It’s fair to say that there’s a big difference going from smolt to a grow-out fish in salmon farming. We have seen over the years that even going from 80- to 100-gram smolts to big smolts weighing 500 to 700 grams is challenging. But it is challenges like these that drive the technology suppliers and the farmers to get together and develop their understanding.”

Collective knowledge

CEO Roy Høiås of global investment firm Lighthouse Finance provides financing solutions to the seafood sector

Over the past year to year-and-a half, RAS technology suppliers have enhanced their services by farming alongside clients in order to fine-tune techniques and provide ongoing support long after the facility is up and running, observed Høiås.

“The supplier of RAS technology is becoming a part of the value chain with their clients. That’s a very promising development because we have seen that some suppliers that are operating their own R&D facilities have the knowledge of, for example salmon farming, in their own environment, with their own equipment. This is a big development for RAS. That technology suppliers are now offering as a part of the solution to farm alongside their clients over the next three to five years is obviously going to de-risk operations in the future.”

Høiås and Tang noted that one reason technology supplier AquaMaof is well defined in the market is because their solutions are not simply a technology platform; they are farming solutions. The Israeli company has two RAS-focused R&D centers, one of which is dedicated to proving the technology in growing salmon to market size and for training staff of its technology clients. That R&D center, located in Poland, is also a full-fledged farm operating under the name Pure Salmon. The facility has produced “several batches” of market-size Atlantic salmon weighing 4-6kg since 2017, AquaMaof says on its website.

“Their ideas and their concepts come from utilizing the technology themselves in order to bring fish to market in Israel and elsewhere. They’re providing this experience to other entrepreneurs that want to establish land-based farms and utilize their technology,” says Tang, who himself co-founded a private debt advisory firm that eventually merged with Lighthouse.

Hudson Valley Fisheries, which raises steelhead in a land-based farm in Upstate New York, wants to help build a RAS-savvy industry workforce.

“That’s really part of our goal – it wasn’t when we started but it is now – to help train the next generation of fish farmers. Every article you read these days say the talent pool for aquaculture worldwide is somewhat limited,” says founder and CEO John Ng.

As to how he would do that hasn’t been mapped out, but Ng knows he’s surrounded by educational institutions that have aquaculture-related offerings that he could collaborate with.

“We have a number of internships. New York has, surprisingly, a number of schools that have good aquaculture programs. About an hour and a half away from us is SUNY Cobleskill, which has a small indoor RAS system where they are raising brown trout. There’s also Cornell in New York, which has an aquaculture department,” says Ng.

A Business reality

Mortality episodes are not surprising for Høiås. He believes losses to livestock are part and parcel of farming.

“If you go back to the conventional farming in the fjords in Norway and you look at that journey from the 1980s to today, it’s similar. There were good years and bad years; it was a learning process. Farming salmon to maturity in RAS is also a learning process. And farming of biomass obviously has risks but it also has rewards. That’s where we see there would be a lot of learning; then you will see solutions.”

Tang says mortalities are not particular to land-based operations either. The death of one million fish when storms hit Bakkafrost’s ocean cages in the Faroe Islands in March goes to show no one is immune, he says.

“It is an element that’s part of farming anything that is alive. You’re going to have issues growing them, you’re going to have issues with mortality, disease, etc, that you can’t necessarily predict easily. They’re not always subject to formulas and these are not data bytes.”

But while there other land-based farms being built around the world — roughly 40 at last count — Atlantic Sapphire has the fortune, or misfortune, of dominating the news because it is building the largest of them all. Its Miami, Florida facility is designed to produce 220,000 MT of head-on-gutted Atlantic salmon by 2030. News drives the company’s stock price on the Oslo Stock Exchange in one direction or the other.

“In all fairness to Atlantic Sapphire, I hope the market will not compare the brand new solutions that are building up in the US facility with the old site in Denmark,” says Høiås.

But he stressed the importance of being upfront to the market about the risks. “It is important to have open communication and to prepare the market for setbacks. There will be times one will lose biomass, but one will put new fish in and start again. It’s the nature of the business. It is a challenge. But I’m less afraid of it today than I was three years ago.”

An investable business plan will always reflect the potential risks in their projections, adds Tang.

“One of the things that we often work on with our investors in terms of these businesses is to recognize that there may be a need for additional capital support in their financial projections to compensate for these kinds of issues, and to be conservative towards that analysis,” says Tang.

He cited as an example a yellowtail land-based facility that Lighthouse is funding in Chile: “We’re adding an additional six to nine months of working capital for losses and incidents like those we’ve seen at Atlantic Sapphire to ensure the business can survive the unpredictability that can accompany farming.”

RAS suppliers are now offering to farm alongside their clients. This will help de-risk the land-based farming evolution taking place in aquaculture.

– Roy Høiås, Founder & CEO

Lighthouse Finance

AquaMaof R&D and Training Center in Poland for Pure Salmon staff and the staff of AquaMaof’s clients Photo: AquaMaof

Betting on the jockey, not the horse

The idea that the quality of people is the best indicator of a RAS project’s long-term success extends to the entrepreneur behind it. Tang makes a strong case for a focus on the entrepreneur and the team when evaluating a project. It is important to ask whether the entrepreneur has some skin in the game, he says.

He did not reject the suggestion that some entrepreneurs are gambling with other people’s money. “There certainly are a lot of plans that we’ve seen where that is the case. So for us, as we look through these business plans, we’re always looking for entrepreneurs that are aligned with our investors. You don’t want somebody running the business that doesn’t have a lot of their net worth tied into these projects. Some entrepreneurs want other people to take all the risk and those are the ones that we avoid.

But he emphasized, the best entrepreneurs share the upside and the downside with investors. “Those projects work out better for everybody.”

Tang continued: “There’s a certain amount of betting you’re doing on this technology. And the risks can vary – a lot. We conduct a project-by-project analysis for our investors. In this analysis, we discern what risks are being taken; does management understand the scope of these risks; and ultimately do they have the skills to mitigate them.”

Investors in unchartered territory

The idea that aquaculture is an unfamiliar territory to the investor community brings another challenge for RAS operators. Tang observed that aquaculture is largely misunderstood, and so is RAS, in fact, more so.

“There’s a sort of a misunderstanding of this particular sector, not necessarily in Roy’s backyard where aquaculture has always been a part of the culture, but certainly in other parts of the world, especially in North America. From a banking and finance standpoint, institutional investors, commercial banks, pension funds and so forth, lack an understanding of this particular space, which is where we think we can add value and create opportunities,” says Tang.

But he observes that interest in RAS operations is starting to emerge among companies that already back traditional ocean-based aquaculture, including insurance companies. “They have actively approached us about how to look at these types of projects and how to analyze the risks to provide insurance to the sector.”

Høiås says what insurance providers are waiting for is “data,” which perhaps is euphemism for success stories.

“Land-based farmers are still not in any position to utilize the financial tools that the conventional farmers are using. They don’t have any data to do the underwriting on and they need to see some of the big volumes to come up first before they can actually do the underwriting,” says Høiås.

That time will come not overnight, but over time, the two acknowledge. “We think that eventually the market will come and see the benefits of land-based farming and be able to provide that support but it will take some more data and a little bit more time.”

In a few years, they expect the RAS space to look very different than how it looks today. Whether mega farms like Atlantic Sapphire will dominate the landscape, or smaller, 10,000-tonne facilities will be more widespread, would be a question of market. Both strategy has its pros and cons, but both can be an important part of the solution, they said.

“We are very excited about land-based farming,” says Tang. “We are supporting on a global level various RAS projects because of the attractive economics and the ongoing environmental challenges such as sea lice increasing the costs in traditional net pen farming.

“Aquaculture in its many forms — from land-based, ocean-based and offshore — is something that the world needs to prevent overfishing the ocean. Fish farming as a whole has a lot of potential for future growth. We don’t think this particular protein category is going to slow down within the next decade or so, especially as the middle class keeps growing in Asia and diets around the world continue to include more fish.”

Advertisement

- Bill could help ease community conflict, stem oyster thefts in Maryland

- Google sister company helps usher in precision aquaculture