The great potential of wolfeel and rockfish

June 25, 2015

By Matt Jones

Conserving the species is a catalyst for farming wolfeel and rockfish.

Conserving the species is a catalyst for farming wolfeel and rockfish.Shannon Balfry, Director of the Aquatic Animal Breeding program at the Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Center (VAMSC), says her research with the native Pacific wolfeel and rockfish is starting to see encouraging results but more research is needed.

Balfry’s work, which expands on previous efforts in this field at the VAMSC, is funded through a number of Aquaculture Collaborative Research and Development Program (ACRDP) grants from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. “We’ve done nutritional diets, we’ve done growth performance diets, temperature and salinity tolerance experiments,” says Balfry. “Quite a lot of research has been done over the years.”

The basis for exploring aquaculture production for both species is with resource conservation. Rockfish in British Columbia are susceptible to overfishing due to the length of time to reach maturity and local aquaculture could take some of the pressure off of the wild fishery.

“That could be another tool in our conservation toolbox,” says Balfry. “The whole idea of getting into more aquaculture production of local species was based on conservation concerns. It looks like rockfish could be sustainably farmed in land-based systems and we have a bit of an idea of how that could be economically feasible. Biologically, it seemed to be feasible.”

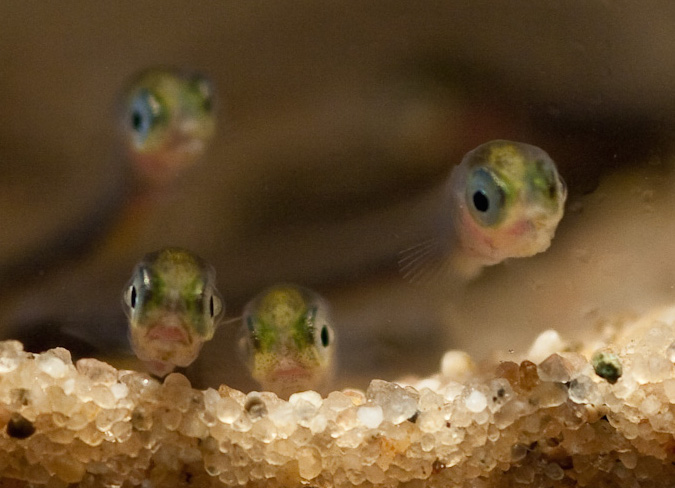

A key challenge is that rockfish give live birth – you must produce live feed in sufficient quantities and quality to get the larvae to survive to the juvenile stage.

“They’re born at 4 millimeters long,” says Balfry. “If we can get them up to, say, a couple of centimeters that seems to be over the hurdle.”

As part of the effort, Balfry contracted Totem Seafarms to handle some of the rockfish grow out. Totem spokesperson Gus Angus stresses the need to continue the research.

“It may be that this species is better suited to tank culture than open-net caged culture,” says Angus. “We aren’t far enough along with this animal to really determine that. We have very few of them, 110 yearlings now on the farm. With that tiny number the fish tend to appear a bit nervous. There isn’t a population dynamic that is encouraging them to be aggressive feeders.”

Angus says that if they could increase the density of fish on site they might see a better feeding response but the regulatory agency, Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s, permission to grow the species came with strict conditions including the limiting the number of fish and stipulating that they be euthanized at the end of the research period.

“We cannot get access to adequate numbers of rockfish from the wild in order to really bring forward the research that Shannon has begun,” says Angus. DFO representatives were unable to provide comment by press time.

In comparison to the rockfish, wolfeels are much easier to work with, says Balfry. While there is no wolfeel fishery in British Columbia, Balfry theorizes that larger wolfeel could be a suitable replacement for certain rockfish species. There’s also the possibility of producing them as a sustainable alternative to unagi eels in the market.

“The unagi eels – the Japanese eel that is used for sushi – is not sustainable at all,” says Balfry. “It’s threatened. If we could grow the smaller wolfeels as a replacement for those eels, that’s another option.”

There remains much research to be done, particularly on the rockfish end but these two species “tick all the boxes for aquaculture’ said Balfry.

“My research is to try to work out some of these production bottle necks,” says Balfry. “We’re not going to be fish farmers ourselves. We want to help create an industry that would support our conservation.”

— Matt Jones