US researchers build case for burbot production

December 10, 2020

By Lynn Fantom

They can grow it, but will farmers come?

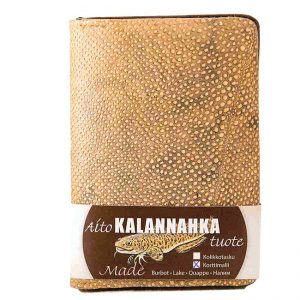

Burbot demonstrate a huddling behavior and perform well in stocking densities higher than those typical for trout

Photo: University of Idaho

Burbot demonstrate a huddling behavior and perform well in stocking densities higher than those typical for trout

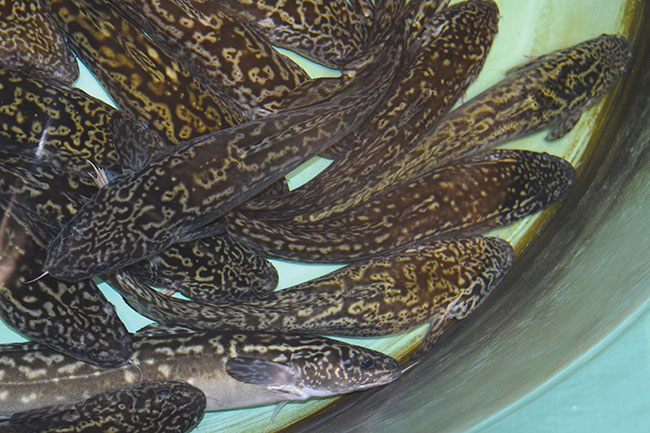

Photo: University of Idaho In Belgium, burbot is at the heart of a beloved traditional Flemish stew. Scandinavians revere its roe. It is said that a French home cook would sell her soul for a burbot’s liver. Today in Finland, a sustainable luxury brand markets burbot handbags for over US$500.

And now it may not be long before burbot (Lota lota) makes waves in North America. “It could be cultured immediately in aquaculture sites that typically raise salmonids,” says Dr Kenneth Cain, professor, Department of Fish and Wildlife Sciences at the University of Idaho.

Following decades of successful work to restore dwindling wild populations in Idaho and British Columbia, researchers are ready to move burbot from the lab to the farm. This coldwater species, the only freshwater member of the cod family, grows well under conditions similar to trout and demonstrates resistance to many salmonid diseases. After years of research, it will come with what is virtually a “user’s guide” for commercial culture.

This practical knowledge — encompassing diet, stocking density, and disease susceptibility — was propelled by a USDA grant to the Western Regional Aquaculture Center. That funded a four-year project at the University of Idaho to examine biological feasibility of raising burbot through all stages, as well as economic viability.

With two years under their belts, the researchers already can pass on considerable know-how to farmers.

Lower-cost feed

For example, Cain’s team recently published encouraging findings about burbot diet during commercial culture. Although juveniles grew better and preferred more expensive marine-type formulations, they performed well on trout-type diets. During the sub-adult growout stage, when a farm incurs the majority of feed costs, burbot did equally well on the marine and trout diets. That signals lower operating costs for producers.

Even more recent work shows there is an opportunity to increase soy protein and reduce fishmeal levels in diets. “Positive from the standpoint of economics, for sure,” says Cain.

What’s more, researchers have documented a one-to-one feed conversion ratio throughout the juvenile growth stages, which is now also being assessed during growout experiments.

“This species is still basically ‘wild’ and has yet to be truly domesticated, like rainbow trout,” adds Luke Oliver, a doctoral candidate in Cain’s lab. As selective breeding occurs, many factors, including growth rates, will continue to improve.

Higher stocking density

Burbot are a benthic species that huddle together during the day and feed voraciously at night. And they can be cannibalistic. That behavior has been managed through feeding protocols and grading out larger fish. They perform better in higher stocking densities, which some researchers hypothesize breaks a social hierarchy.

Idaho scientists have found burbot can be raised at 50 to 60 kilograms per cubic meter, a higher density than trout. However, water quality (particularly ammonia and oxygen) must be kept at levels similar to those for trout. The group is working with Dr Chris Myrick at Colorado State University to further characterize those limits, says Cain.

Disease resistance

As trout farmers continue to grapple with coldwater bacterial and columnaris diseases, fish health and disease resistance are high on their list before they will adopt a new species.

After a disease outbreak of burbot at a commercial facility, scientists took the opportunity to learn more. They isolated two types of bacteria: Aeromonas bacterium and Flavobacterium columnare and used them in experimental infections. Little mortality resulted.

Researchers hypothesized that poor water quality or some type of stress may have set the stage for Aeromonas bacteria to cause a disease outbreak. F. columnare just happened to be isolated in the sampling, since burbot were relatively resistant and did not develop disease following an F. columnare challenge.

These initial findings will help formulate the foundation of disease management methods that will be developed as burbot aquaculture expands.

Farm diversification

Burbot grow well at 15 degrees Centigrade. “This suggests that with little modification a burbot growout production system could be easily and relatively cheaply incorporated into an existing trout production facility, diversifying production,” says Oliver.

Preliminary growout trials have been conducted both at the College of Southern Idaho and some commercial facilities to investigate polyculture with trout. Minimal mortality and no fish health issues in either group resulted.

Cain does note one bottleneck for trout producers who want to diversify: processing. Burbot will not go through the same machines.

Hatchery challenges, opportunities

The best model for developing commercial production of burbot, Cain believes, is for companies interested in burbot culture to rely initially on the lab for hatchery work.

Burbot can be challenging in their early life stages. A long incubation period for eggs and 50 to 60 days of feeding larvae live artemia make it risky and expensive. But research is improving that outlook, too.

“We’re set up to feed-train those at a young stage and to produce juveniles for growout,” Cain notes.

The Idaho researchers are also advancing their understanding of methods to produce sterile burbot through triploid induction. By referencing the parameters for triploid induction in Atlantic cod, they were able to induce triploids in burbot during their very first year. “This would have been much harder without cod as a model,” says Oliver.

What consumers say

If the European experience is any guide, raising burbot offers a number of market opportunities. Its meat, liver, roe, and skin can all be utilized.

To evaluate potential as a food fish specifically, the researchers conducted both a restaurant survey and sensory tasting panel that demonstrated that burbot are, as Cain says, “one of the most promising candidates for commercialization as a food fish.”

In the restaurant trial among 150 customers — 82 percent of which had never tried burbot before — both the flavor and texture of burbot scored high. In fact, 96 percent said they would try burbot again.

Last year, at the Washington State University sensory facility, researchers asked a consumer panel of 84 participants to compare burbot with two prominent aquaculture species: trout and tilapia. Panelists evaluated aroma, flavor, and texture; 81 percent preferred burbot over trout and 87 percent over tilapia.

Moureen Matuha, another Idaho graduate researcher, oversaw the study. She is now developing an “enterprise budget” so that farmers will have pro forma revenue and costs. She thinks burbot tastes like cod and often wishes she had some for dinner.

Until commercial production, though, lucky anglers are the only ones bringing burbot back to the home kitchen. Online recipes point to several preparations. Some like it swathed in a blanket of bacon, almost like scallops. Others treat it as a stand-in for cod. But a clear favorite seems to be “Poor Man’s Lobster,” which requires simmering in salted water with lemon juice. Then, just dip in melted butter.

Advertisement

- Morenot Canada offers complete package

- Government faces pressure as B.C. fish farm licenses near expiration