Big plans for innovative salmon venture proposed for Maine

June 30, 2021

By Lynn Fantom

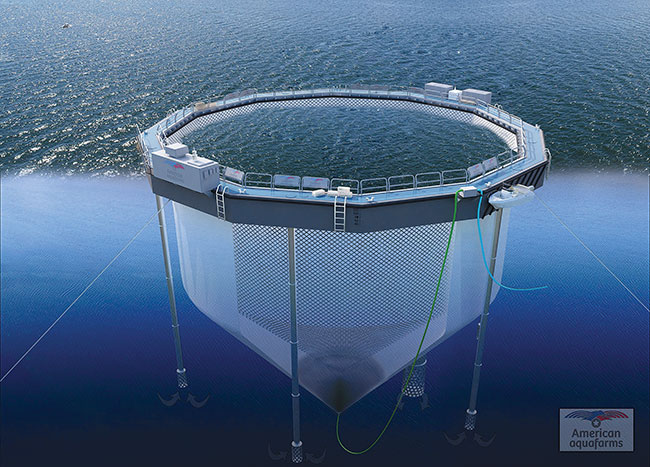

American Aquafarms to invest $250 million in world’s largest full-cycle facility based on floating cages

American Aquafarms is applying for two

lease sites of 60.3 acres each that will feature

30 floating close containment pens in Frenchman Bay. Image: American Aquafarms

American Aquafarms is applying for two

lease sites of 60.3 acres each that will feature

30 floating close containment pens in Frenchman Bay. Image: American Aquafarms Unlike many management teams who trial technology new to them on a smaller scale, American Aquafarms is starting out big. The Norway-based entity, founded in late 2019, is making its first foray into salmon farming with a floating semi-closed containment system that itself was first marketed at commercial scale in 2019.

If approved in Maine, it will be the first deployment of Ecomerden’s “eco-cage” in the US and, experts believe, the first such semi-closed system in the country. The goal is to produce 30,000 metric tons of Atlantic salmon by 2024.

The venture comes at a time of robust exploration of semi- and closed-containment technologies. “We see a clear new direction politically worldwide, in both Canada and Norway, where the governments are starting to demand using other systems to make sure that we can increase production and, at the same time, take care of the environment,” says American Aquafarms chief executive Mikael Rønes.

Another pioneering aspect of the young company’s plan is to raise salmon to harvest size in the “eco-cages,” a benchmark Cermaq Canada is now testing. “The primary use [in Norway] is to produce a smolt and post-smolt,” notes Eirik Jors, American Aquafarms vice president.

The company is applying for two lease sites of 60.3 acres each in Maine’s Frenchman Bay. Each mooring system will tether 15 pens, along with a barge for power generation, feed, waste, and monitoring technologies.

It remains to be seen whether or not this is all too much for a busy harbor between two sites of Maine’s historic Acadia National Park. The company filed its pre-application with the Maine Department of Marine Resources on March 3 and has a “very comprehensive and very rigorous” process ahead if it gets a green light to proceed, according to Sebastian Belle, executive director of the Maine Aquaculture Association (MAA).

“Things may take time, but we are here for the long run,” Rønes says. “We do not have external investors we need to answer to on why things are slowing down or moving faster.”

American Aquafarms is co-owned by Rønes’ investment company Global AS and Amar Group, which is led by aquaculture heavy-hitter Bjorn Apeland.

Rønes, who grew up in Norway surrounded by aquaculture, pursued an early career in finance. In 2008, he was convicted of defrauding investors and sentenced to four years in prison. Later, he saw the potential of cod as a species for aquaculture and, in 2017, founded a company now known as Norcod. He exited in 2019, and Norcod went public in 2020.

Rønes sees himself as an entrepreneur who has defied those who tell him things can’t be done. “I’ve gone against the wind,” he says.

American Aquafarms plans to invest about $250 million in the end-to-end operation that includes both hatchery and processing operations on an 11-acre site. It is envisioned as the world’s largest full-cycle facility based on semi-closed floating cages. Rønes says the scale is driven by the goal to keep the facility humming 52 weeks a year.

That volume is a step in satisfying the appetites of American salmon lovers. Within a 24-hour truck drive, Maine farmers can reach 130 million consumers, notes MAA’s Belle. Because of its quality, Maine seafood typically fetches prices 10 to 20 percent higher in the marketplace, he adds.

For American Aquafarms, Frenchman Bay in Maine met criteria for water temperature, depth, and shelter from harsh weather. That is of particular concern as Atlantic coastal storms, known as nor’easters, increase in intensity due to climate change. In fact, engineers say that the main challenge of a floating closed containment structure is to obtain a calm environment suitable for fish farming during high energy conditions.

(L-R) Norwegian entrepreneurs Eirik Jors and Mikael Rønes eye Maine for its cold, deep water and working waterfront. Photo: American Aquafarms

Ecomerden touts its cage as “able to withstand a long wave resonance period…on more exposed sites.” Such equipment standards, as well as operational produces (no sure if you meant to have produces here), will be part of the containment management plan American Aquafarms must submit to Maine regulators as it vies for permits.

In addition to environmental conditions, Maine’s heritage as a working waterfront attracted the Norwegian investors. Aquaculture is a key industry in Maine’s 10-year economic development plan, notes David Farmer, spokesperson for American Aquafarms. Although robotics will bring operational efficiencies, about 90 jobs sea-side are anticipated, with even more in processing.

But those jobs may not offset the concerns about “industrialized” aquaculture among environmentally and tourism-minded Mainers. When the first commercial-size Ecomerden cage was installed in Norway in 2019, one observer said it resembled “a spacecraft from one of the Star Wars movies, hanging on steel wires.” Maine’s tolerance for an interplanetary invasion of 30 such cages among its quaint lobster boats and kayaking tourists remains an open issue.

Every project of any size in Maine has to overcome the “uncertainty of something new,” adds Farmer, who is based in Maine. “Is the visual impact of multi-story cruise ships coming in and out of Frenchman Bay any worse than the lights from fish pens? But we are familiar with the cruise ships,” he says. “I would just posit that if we tried today to build a lighthouse in the state of Maine, we could not do it.”