Canadian study to explore probiotics’ potential in battling sea lice

November 14, 2016

By Liza Mayer

Gut may provide clues to salmon’s resistance to sea lice — or lack thereof

Gut may provide clues to salmon’s resistance to sea lice — or lack thereof

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) scientists Dr Shawn Robinson and Steven Leadbeater are studying sea lice to find new ways of combating these pests at farms along Canada’s East Coast.

Traditionally, sea lice are managed by good animal husbandry practices — area management, fallowing between “crops” of fish, and low density stocking — and in-feed and bath treatments. Despite some success, DFO says sea lice on the East Coast are becoming resistant to some treatments, prompting the need to find alternative solutions for managing sea lice infestations.

New area of research

Steven Leadbeater is exploring a new area of sea lice research that connects to salmon breeding programs. In 2013, Leadbeater embarked on a laboratory study to examine the natural resistance to sea lice of 50 different families of salmon broodstock provided by Cooke Aquaculture in St George, New Brunswick, to determine if some are more resistant than others. His findings will be combined with probiotic-type research to see if the same salmon families have bacteria or bacterial bio-markers in their gut or mucus that makes them more resistant to sea lice.

“Broodstock samples are being analyzed at Laval University. If results show that some salmon families have fewer sea lice counts and contained certain species of bacteria, we will then try applying a beneficial probiotic — perhaps in feed — to fish that don’t naturally have that resistance,” says Leadbeater. “Such a finding would introduce the potential for industry to selectively breed families of salmon that naturally support bacteria known to lower sea lice landings and infections.”

Ecology and sea lice

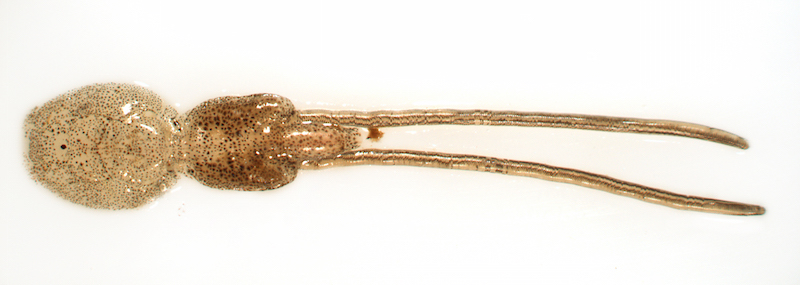

Ecological research to date has primarily investigated sea lice at an age when they attach to fish. Dr Robinson, however, is focusing his attention on understanding the larval planktonic stage of sea lice, when they are most abundant.

“A female sea louse produces 300 to 500 eggs at a time, with five to eight broods a year. It takes 40 to 50 days to grow from larval stage to reproductive adult, so if conditions are suitable for larvae to encounter a host, there is potential for rapid population growth,” says Robinson.

Robinson’s team studied the distribution of planktonic sea lice larvae in the Bay of Fundy and found virtually all of the larvae occurred around salmon cages, while none were present in comparative locations away from operational salmon farms. They were also distributed throughout the water column (top to bottom), not just in surface waters as the scientific literature of earlier larval studies reported.

“These results suggest that if the problem is internal to the farm, then solutions for sea lice infestation may also be generated at the farm level,” says Robinson.

Future alternatives

Cooke Aquaculture approached Dr Robinson to help test a new thermal de-lousing system they had developed — a mobile warm water shower that could be used on-site to remove sea lice. Cooke received $3.2 million from the Canadian government in September to help fund its research (see side bar). The water used in the system is recycled, reheated and filtered to capture sea lice eggs so they don’t re-infect the salmon cages after the fish are treated.

“Preliminary results indicate that thermal delousing is quite effective,” says Robinson. “The company plans to continue field trials to determine the ideal water temperature, fine-tune the engineering of the equipment, and measure its overall effectiveness. Our team will continue to provide them with critical scientific advice and analyses during these trials.”

Robinson adds: “The evolutionary and ecological relationships between host species and their parasites have developed over millions of years. These can be very complicated and sophisticated, which means our approaches to aquaculture have to be equally sophisticated and well-planned. That is the challenge for the future.”

Aquaculture research at DFO is conducted under its Aquaculture Collaborative Research Development Program (ACRDP) and the Program for Aquaculture Regulatory Research (PARR).

– Liza Mayer

Advertisement

- Study compares effects of Ike Jime and humane stunning technology on maintaining freshness during processing

- Cooke Aquaculture working on new sea lice solution